The recent Supreme Court decision regarding Samuel Alito’s stance on wetlands has been the subject of sensational headlines, such as “Samuel Alito’s Assault on Wetlands Is So Indefensible That He Lost Brett Kavanaugh.” However, despite the media’s penchant for playing up dissent at the Court, the justices unanimously sided with the petitioners in this case. While they disagreed on the proper standard at issue, they unanimously agreed that the government’s actions were wrong.

While dissenting opinions can be dramatic and foreshadow future litigation, the Supreme Court is not as divided as the media would have us believe. In fact, just under half of the cases decided each term are unanimous, meaning that one side has been able to persuade all nine justices to rule in their favor. At Pacific Legal Foundation, where the author works, they have won two unanimous Supreme Court rulings in recent weeks.

Historically, the Court has had an average of over 80% unanimous rulings per term. However, after the Judges Act of 1925 gave the justices more leeway to pick which cases to hear, they increasingly limited review to cases presenting novel, thorny legal questions that divided lower courts. As a result, the proportion of unanimous rulings decreased to 40-50%, where it has remained since the 1950s.

Throughout the Court’s history, many chief justices have tried to steer the ship in the direction of broad agreement. For instance, John Marshall used unanimous rulings to secure the Court’s equal footing with Congress and the presidency during our country’s early years. More than a century later, William Howard Taft discouraged his colleagues from penning dissents, explaining that he thought it was “more important… to stand by the Court and give its judgment weight than merely to record my individual dissent.”

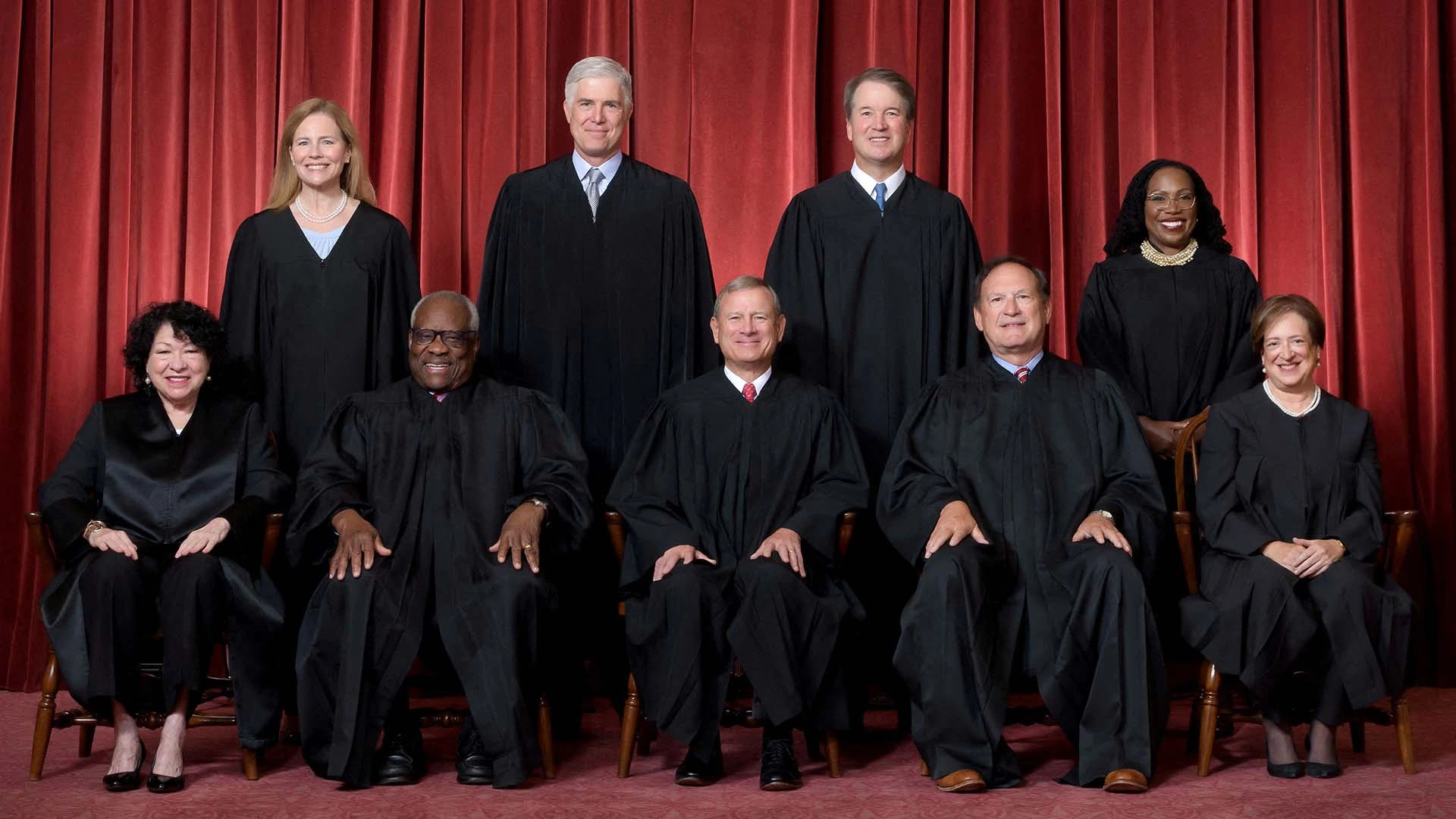

However, the chief justice is not always able to keep everyone on board. While mainstream-media coverage of the Roberts Court often portrays it as a rubber stamp for Republican policies, the number of cases that appear to fall along “partisan” lines is relatively small. There are often surprising results, with shifting coalitions and odd couples. Justices appointed by the same president don’t always see eye to eye, and even textualists have internecine fights.

Instead of viewing the Supreme Court as comprising two monolithic blocks that vote according to the party of the president who nominated them, we should recognize that the justices are individuals with their own idiosyncrasies, backgrounds, and approaches to the law. If we look beyond the headlines, we’ll find plenty of cases where justices find themselves in agreement. So the next time we see a clickbait headline hyping a deep divide among the justices, we should remember that the facts show the Supreme Court isn’t nearly as divided as we may think.