The new exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, titled “Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby,” has sparked controversy and debate. Despite the mixed reviews, the exhibition offers a valuable reappraisal of Pablo Picasso’s work 50 years after his death. The exhibition consists of three components: a selection of around 50 Picasso paintings, prints, drawings, and sculptures, a showcase of contemporary art by women from the museum’s collection, and a tribute to Hannah Gadsby’s stage performance, “Nanette.”

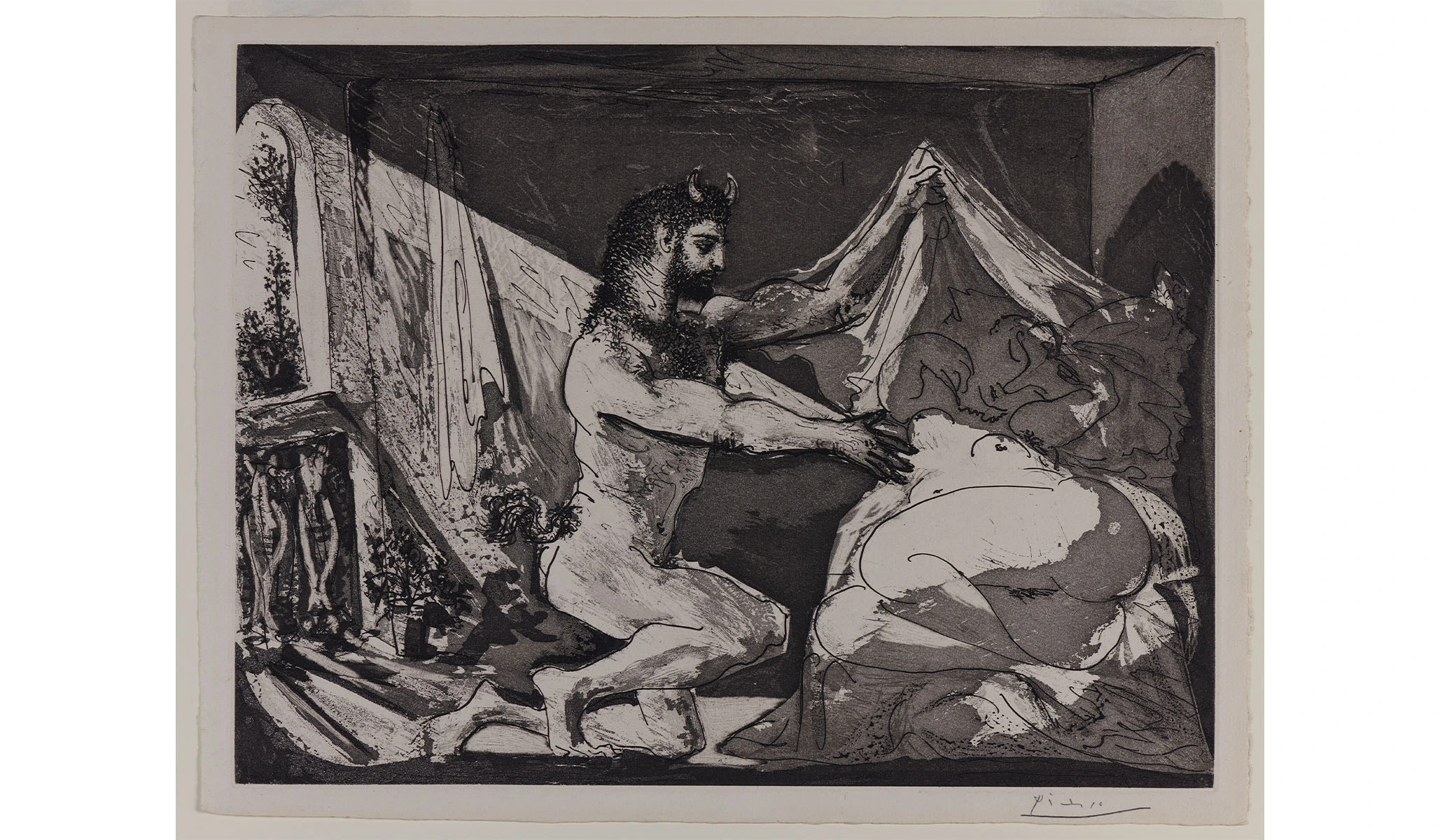

The Picasso section of the exhibition features works from early in his career to the late 1940s, offering a glimpse into the breadth of his artistic talent. While cherry-picking from his vast oeuvre is inevitable, the paintings on display are impressive, with a significant portion loaned from the Picasso Museum in Paris. Picasso’s prowess as a painter, draftsman, and printmaker is evident in his iconic Vollard Suite, a series of Minotaur etchings published in 1939.

The exhibition also highlights the Brooklyn Museum’s commitment to collecting and showcasing contemporary art by women. Unlike many other museums, the Brooklyn Museum actively acquired works by women artists, including the Guerrilla Girls, Joan Semmel, Louise Bourgeois, Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons, May Stevens, and Mickalene Thomas. These artists, often in their peak feminist mode, contribute powerful and thought-provoking pieces to the exhibition.

Hannah Gadsby, an Australian stand-up comic and writer, serves as the inspiration for the exhibition. Her stage performance, “Nanette,” is featured in a video gallery within the exhibition. Gadsby’s critique of Picasso revolves around his alleged seductive, misogynistic, and psychologically troubled nature. While her perspective may not resonate with everyone, her presence in the exhibition adds an edgy element and aligns with the museum’s desire to attract attention.

The exhibition’s galleries, located near the museum’s entrance, provide an intimate and somewhat claustrophobic setting. The space is filled with Picasso’s works, many of which are on paper, creating a tomb-like atmosphere. The wall colors, ranging from tomato-red to rich blue and eggplant, evoke a sense of an older world. As visitors progress through the exhibition, the wall colors gradually lighten to accommodate more contemporary works.

The exhibition begins with a striking painting by Cecily Brown titled “Triumph of the Vanities II.” This massive artwork, displayed over the entrance, appears abstract at first glance but reveals intricate details upon closer inspection. The painting references the concept of the “bonfire of the vanities” and features figures engaging in an operatic frenzy, including portraits of Picasso, Jackson Pollock, and Donald Trump.

The Guerrilla Girls, an artist collective from the 1980s and 1990s, are also prominently featured in the exhibition. Their satirical poster, “Code of Ethics for an Art Museum,” criticizes the art world’s tendency to prop up white male artists and highlights issues of nepotism and gender inequality. Adjacent to the Guerrilla Girls’ work is a portrait of Linda Nochlin, an art historian known for her essay on the invisibility of women artists in museums and the art market. The portrait, painted by Philip Pearlstein in 1968, depicts Nochlin in a position of power, challenging traditional gender roles.

Kaleta Doolin’s sculpture, “Improved Janson: A Woman on Every Page #2,” is a provocative piece that critiques the lack of representation of women artists in art history textbooks. Doolin carves an opening in H. W. Janson’s “History of Art” book in the shape of a vulva, highlighting the need for inclusivity and recognition of women artists.

While the exhibition touches on Picasso’s problematic views and relationships with women, it also showcases his artistic genius. Quotes from various artists and critics emphasize Picasso’s inventiveness and his ability to capture the human form in unique ways. The exhibition also delves into Picasso’s fascination with Greek and Roman mythology, presenting his mythological subjects in the context of the Old Masters and exploring the themes of power, ambition, and human depravity.

The inclusion of works by women artists throughout the exhibition challenges the notion of Picasso as the epitome of a patriarchal, capitalist society. Artists like Joan Semmel, Kiki Smith, and Rachel Kneebone express their admiration for Picasso’s groundbreaking contributions to art while asserting their own artistic identities and perspectives.

Overall, “Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby” offers a nuanced and multifaceted exploration of Picasso’s legacy. While some may find Gadsby’s commentary juvenile or unnecessary, the exhibition provides a platform for diverse voices and encourages visitors to engage with Picasso’s complex and evolving artistic vision.