National Review Capital Matters is celebrating the 300th birthday of Adam Smith with a monthly Adam Smith 300 series throughout 2023. Each essay in the series will be written by various students of Smith’s thought and will be published on the 16th day of each month, in honor of Smith’s birthday on June 16. The series is being curated by Daniel Klein and Erik Matson of George Mason University, along with Dominic Pino. Previous essays in the series can be found here.

Adam Smith is often referred to as the father of economics and a founder of classical liberalism. However, these portrayals tend to overlook the fact that Smith’s ideas were shaped by his reading and participation in debates with his peers. Smith was a product of the Scottish Enlightenment, which took place in the middle years of the 18th century and was part of a wider European Enlightenment, known as the “Age of Reason.”

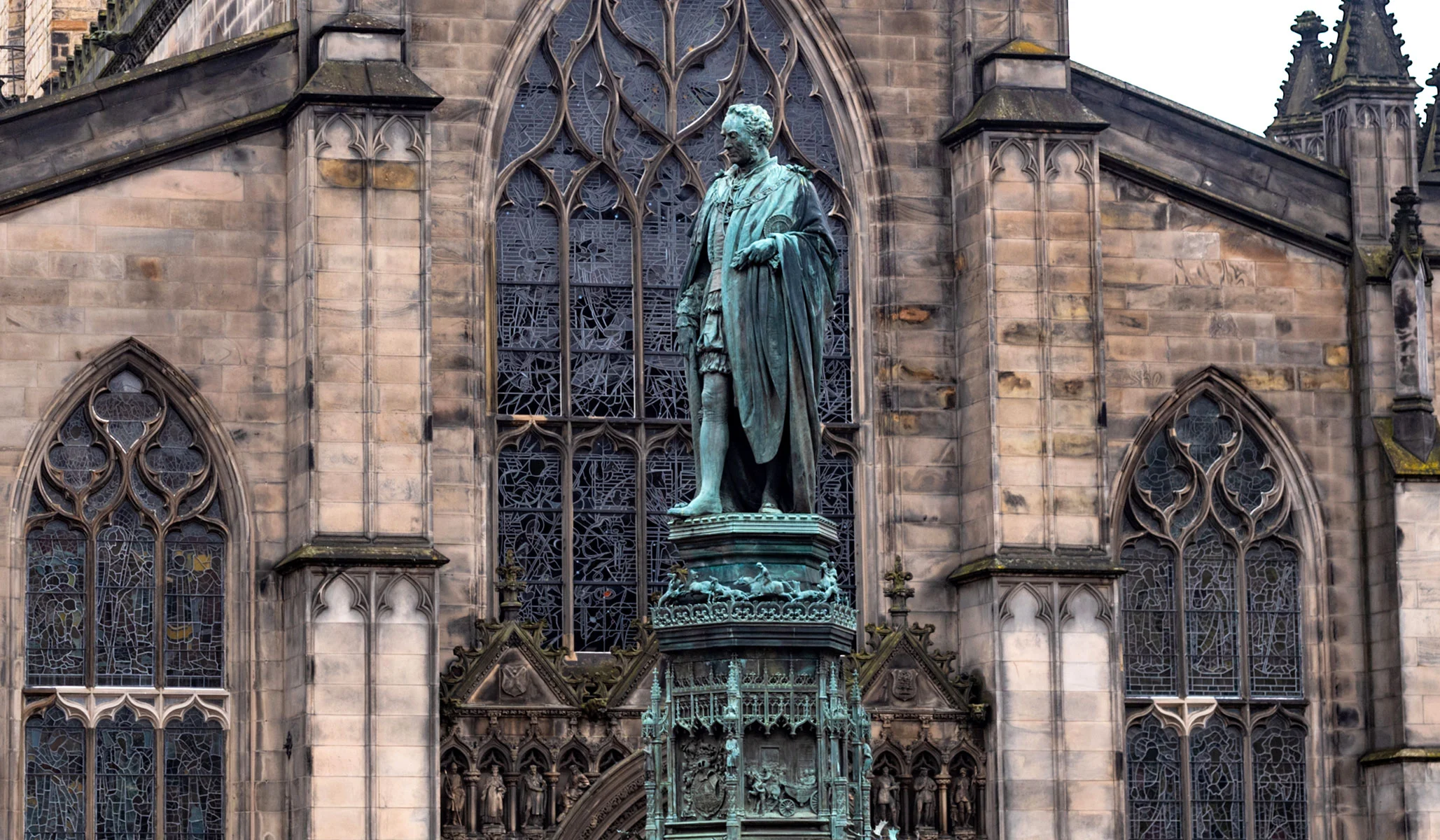

The Scottish Enlightenment was a time when science, progress, and freedom of expression and activity came increasingly into the intellectual vanguard. This was no coincidence, as Scotland had emerged from a traumatic 17th century marked by religious fanaticism, civil war, famine, and national bankruptcy. After the Union of Parliaments with England in 1707, Scotland experienced a long period of relative civil and political security as part of the new state of Great Britain. With political stability came economic transformation as Scots gained access to new markets in Great Britain and its colonies in the Americas, leading to spectacular economic growth, urbanization, and rapid social change.

The literati, a tight-knit group of Scottish intellectuals, were at the center of the Scottish Enlightenment. They came from similar middle-class backgrounds and benefited from the Presbyterian emphasis on literacy and Scotland’s excellent local schools and universities. Teaching in the Scottish universities had been transformed by the introduction of the latest work in science and moral philosophy by figures such as Colin Maclaurin and Francis Hutcheson. Hutcheson, sometimes referred to as the “father” of the Scottish Enlightenment, developed the style of philosophical education that became the backbone of the Scottish universities. His moral-philosophy curriculum ensured that students read widely across ethics, jurisprudence, aesthetics, politics, sociology, and philosophy of religion. Scottish education had a social as well as an intellectual function, and this notion deeply influenced Adam Smith’s understanding of what was expected of him when he took over the chair at Glasgow that Hutcheson had occupied.

The ambitious young men of the literati found their way into jobs in the universities, the Scottish state church, and the law. Among their number were figures such as Adam Ferguson, the “father of sociology”; Henry Home, Lord Kames, a judge and critic; Joseph Black, who discovered carbon dioxide; James Hutton, father of geology; Hugh Blair, the first professor of English literature in the world; Thomas Reid, who succeeded Smith at Glasgow; the historian and church leader William Robertson; the engineer James Watt; the architect Robert Adam; and medical men such as John Gregory, William Cullen, and the brothers John and William Hunter. At the center of it all stood Smith’s great friend David Hume, the brilliant philosopher and historian whose ideas proved so influential on Smith’s intellectual development.

Many of the literati were ministers of the Church of Scotland, called the Scottish Kirk, and worked to introduce enlightened ideas to the Kirk, seeing it as a potential vehicle for improvement. This marked the Scottish Enlightenment as decisively different from the French Enlightenment, where those known as the philosophes were implacably opposed to the Catholic Church and drew a sharp line between enlightenment and established religion.

Members of the Scottish Enlightenment could see the benefits of economic development, and they wanted to encourage the process. The idea of “improvement” became central to their sense of themselves as a group. Clubs such as the Edinburgh Society for Encouraging Arts, Sciences, Manufactures, and Agriculture, the Select Society, the Poker Club, and Adam Smith’s own Oyster Club, would meet to share the latest advances in knowledge. The clubs debated ideas from around the world along with the latest Scottish ideas. The leading Scots corresponded with and met the leading intellectuals of the time, with visitors such as Edmund Burke and Benjamin Franklin welcomed into what the Scottish novelist Tobias Smollett described as “a hotbed of genius.”

Smith’s interest in society, morality, and political economy was shaped by the Scottish Enlightenment. He believed that the attempt to generalize from the experience of a particular country would allow for the understanding of universal features of social life. Drawing on the work of earlier political economists, Smith attempted to create a scientific study of what he could see going on around him in Scotland, Britain, and the British Empire. His Theory of Moral Sentiments was an attempt to apply science to our understanding of how people make moral judgments. The goal was to examine how people come to form ideas about how they should live their lives, and to inform a new theory about the virtues appropriate for a commercial society. The point was not to preach virtue